There’s a particular mood you settle into when you start a new Soulslike. You don’t boot up a game like Wuchang: Fallen Feathers expecting comfort — you brace yourself. You lean into uncertainty, ready for the harsh learning curves, methodical combat, and opaque storytelling that’s long been synonymous with the genre. And yet, playing Wuchang for the first time, what struck me wasn’t only how firmly it checked these familiar boxes, but how confidently it painted something new, hauntingly beautiful, atop that well-trodden canvas. Wuchang: Fallen Feathers for all its derivations, manages to be intimate and grand at once, a dark fantasy straight out of Chinese myth and painterly tragedy that continually surprised me over its 40+ hour journey.

The game starts in disorientation not just narratively, as Wuchang awakens among fog, plagued by amnesia and a mysterious illness known as Feathering, but also mechanically. The opening hours drip-feed the systems: stamina-based fight, stat-heavy builds, a daunting yet elegant skill tree called the Impetus Repository, and the familiar punishing checkpoint cadence we all know too well. But this isn’t another FromSoft imitation. Within a few hours, I realized that Wuchang didn’t want me to mimic what I learned from Dark Souls or Bloodborne; it wanted me to build something new from the ashes.

Combat in Wuchang: Fallen Feathers is a complex dance, a kind of ritualistic precision that relies not only on your reflexes, but your relationship with the weapon you wield; what a variety of weapons you’re given. From spears to dual blades, from one-handed swords that dance in and out of range to cumbersome axes that crush enemies in slow, devastating arcs, each one defines your rhythm. The mechanics go in-depth when you unlock your Discipline skills and weapon abilities, many of which are core to surviving hard battles. It reminded me of Final Fantasy X’s Sphere Grid, a massive branching progression system, where every new node was a stat bump, and a philosophical shift to approach a fight.

There’s a moment around the ten-hour mark where I discovered a Discipline, Crescent Moon for my longsword — a skill that lets you close distance and then vanish out again, leaving a small AoE burn effect in your wake. It was a great use to me as it aligned with the kind of Wuchang I wanted to be like evasive, adaptive, always circling danger rather than charging straight into it. That freedom to play how you think and feel, to shift your battle identity as the world grows darker around you, is one of Wuchang’s greatest strengths.

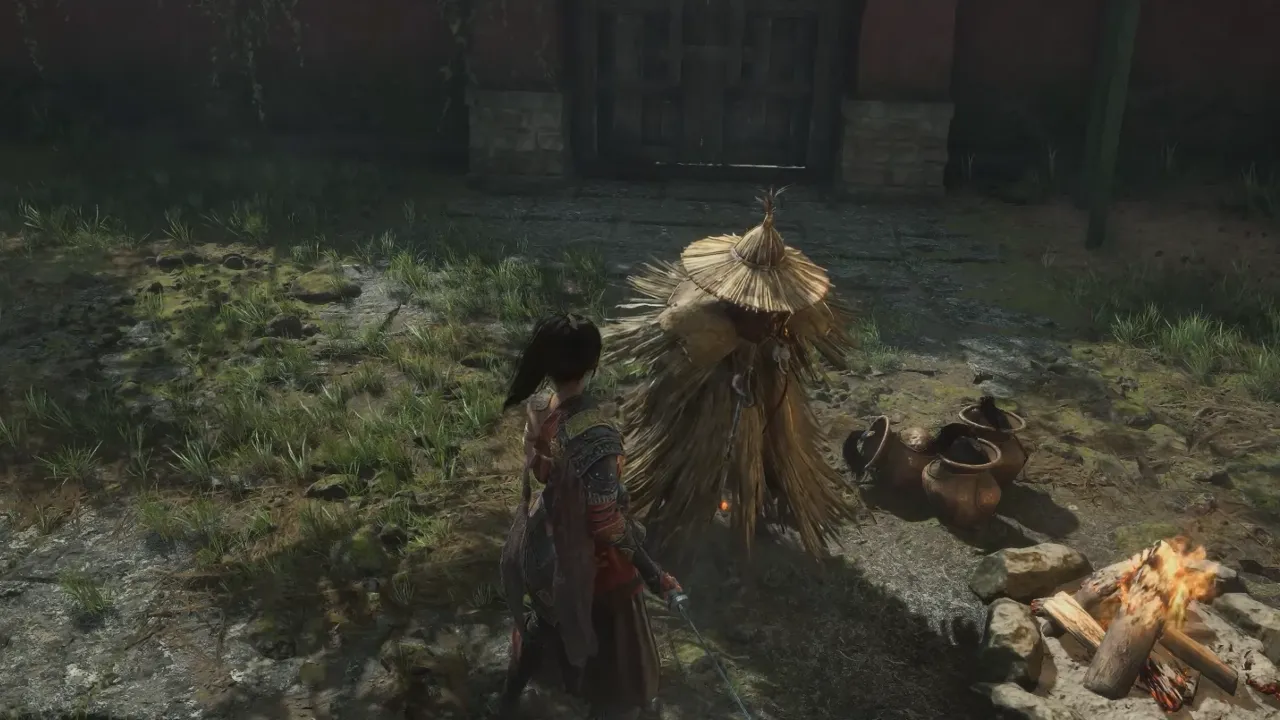

Considering the Wuchang’s world, which is set in China’s historical Ming Dynasty, I’ve played my fair share of grim fantasy, but rarely have I wandered through such a lovingly realized nightmare. The world Leenzee Games built looks like a haunted scroll painting brought to life, mountains curl like dragon spines, villages are nestled into damp, fog-soaked valleys, and twisted temples loom from above with grotesque, bird-like statuary bleeding from the rooftops. There’s beauty here, but it’s always tinged with rot. A fragile elegance persists even as everything decays. I paused constantly, not just for safety, but to take it all in. Every area is visually special and unique, yet all feel connected, part of a cohesive world that’s been slowly hollowed out by the Feathering disease, which is a sickness that consumes memory and humanity alike, until all that’s left is a beast, and feathers.

The design of the world itself is classic Soulslike with looping, dense, filled with secrets and shortcuts that reward curiosity. But it’s not a copy-and-paste but layered and atmospheric, with moments that caught me off guard with design. One stretch in particular comes to mind is a desperate sprint through a poison-riddled cave while an unseen enemy builds a Despair affliction simply by watching you. That moment wasn’t “fun” in the traditional sense, but it was exhilarating. Wuchang doesn’t only challenge you mechanically; it unsettles you emotionally.

Wuchang does more than simply challenging you; it unsettles you with emotional elements.

The story, on the other hand, is where the experience loses some cohesion. I was initially happy and drawn in by the mystery of Wuchang’s identity and the Feathering’s implications. There’s something quietly terrifying about forgetting who you are before you even die. And yet, despite this compelling premise, the story began to lose me as the game wore on. NPCs appear, vanish, and reappear with little to no explanation. Names are dropped with no context. Characters with seemingly critical arcs often seem flavor text in a world that doesn’t quite know how to thread them together. While the game is laced with stories such as item descriptions, environmental cues, and cryptic monologues, the storytelling looked more functional than essential to me.

Still, it’s not without thematic weight. I was particularly struck by the way the game treats perception. Because Wuchang is seen as someone in the early stages of turning, many human enemies don’t attack because of malice, instead out of fear. To them, you are the monster, and that affects gameplay. Killing humans increases your Madness stat, which if left unchecked, spawns an evil version of yourself that can invade your world. And that version can heal. It’s a clever moral system; every swing of your blade is a choice not between good or evil, but between survival and something more nuanced. Sometimes the scariest thing isn’t what the world thinks of you, it’s when you start to believe it yourself.

What impressed me most, though, was how the game constantly gave me reasons to evolve. I never stuck with one weapon for more than ten hours. Not because I was bored, far from it. But each new environment, enemy type, and boss demanded a new rhythm and a new approach. And respec is free, which removes the friction from experimentation. That’s something I wish more RPGs embraced: let players make mistakes, then let them grow from them without punishment.

But I’d be lying if I said it was all smooth sailing. Wuchang’s difficulty curve is… erratic. The first half lulled me into a sense of earned confidence like I was adapting well, learning the parry timings, managing my stamina, and building my character effectively. But then came Commander Honglan, a boss who made me question if I understood the game at all. She was less a difficulty spike and more of a wall. Her attacks were relentless, her openings almost non-existent. Perfect dodges became mandatory, and even then, she punished hesitation brutally. It wasn’t that she was impossible (I beat her eventually), but the fight lacked rhythm. I wasn’t dancing with death, but I was scraping at a brick wall, trying to find a crack.

That same inconsistency appears later, too. Boss fights swing between fair but demanding and borderline broken. Some of the most beautifully designed enemies offer almost no opportunity for retaliation. When I did everything right, when I dodged right, read the pattern, executed my build’s strengths, I still had nowhere to push back. It’s a frustrating feeling knowing the game wants you to be creative and expressive, but sometimes it forgets to give you the space to do it.

Still, even when the bosses tested my patience, it was hard to stay frustrated for long, thanks to the reason that Wuchang continued to show moments of brilliance outside the arena. What helped me stay engaged was more than the gear I collected or the challenge I faced, it was the world constantly inviting me to look closer, to learn, to adapt. Shrines (which act as standard Soulslike checkpoints) were spaced with just enough generosity to feel fair without ever coddling. Further, the level design, let me linger on that for a moment, it’s superb.

There’s a layered elegance to how environments connect to each other. A twisting mountain path links back to a collapsed bridge I passed hours earlier. A dilapidated temple that looked isolated reveals a shortcut to an underground chamber full of lore and enemies I wasn’t ready for. These are the kinds of “a-ha!” moments that gave success to Bloodborne and Sekiro, and Leenzee clearly understood the magic of earned geography.

Even better, Wuchang isn’t afraid to mix tone and pacing. While most areas stick to the sorrowful, decaying atmosphere of the Feathering-plagued world, there are brief shifts such as pockets of eerie tranquility, or desperate sprints that almost give you puzzle chills. One such intense area involved using limited vision to dodge a gaze-based enemy that inflicted instant-death Despair. It was one of the non-combat sequences that still managed to be among the most intense moments I experienced, because it reinforced the game’s core tension: that survival isn’t always about fighting; sometimes you have to navigate the unknown.

And navigating Wuchang is a joy in large part because the systems respect your time. That’s something I didn’t expect going in. Too often, Soulslikes revel in punishing repetition — you die, restart, lose all your currency unless you reach your corpse. Wuchang tweaks this formula, where you only lose about half your Red Mercury (the XP/currency equivalent), and you’re never too far from a Shrine. That doesn’t mean the game is easy but it isn’t cruel for cruelty’s sake. In this genre, that’s a subtle but important distinction.

Of course, Wuchang still has its version of punishment — the Madness system. As I mentioned earlier, the more you kill human enemies or die yourself, the higher your Madness meter climbs. When it peaks, a demonic version of yourself spawns into the world and guards your lost Red Mercury. It’s a simple concept on paper, but it adds the right amount of narrative flavor and gameplay risk. Sometimes I used it tactically by letting my “other self” draw aggro from surrounding enemies. Other times, it became a desperate scramble to avoid being cornered by a mirror image that fought just like I did, but harder, faster, and without mercy.

There’s something poetic about that, to be honest. You don’t only fear the world in Wuchang, it’s what the world is making you become. Madness is a creeping shadow that’s as much about internal decay as external threat. Thematically, it pairs correctly with the story’s central conceit: a woman slowly losing her memories, watched with suspicion by those she might’ve once called kin. And the more I leaned into power, the less human she felt.

That’s where the narrative almost hits something profound even if it never quite pulls it together. There’s a fantastic idea underneath everything that Bai Wuchang is both heroine and horror. Her affliction gives her power, but it also separates her from the people she’s trying to save. Although the world’s inhabitants treat her like a ticking time bomb, they’re not always wrong. The game doesn’t push that duality as far as I hoped, but the groundwork is there, and it’s stronger than most of its more conventional plot beats.

I do wish Bai herself had been a more vivid presence. For a protagonist with a pirate background and a disease mutating her mind and body, she plays things oddly quiet. Leenzee chose to give her a fixed identity, rather than making her a blank-slate avatar, and I respect that decision. But the tradeoff is that she often looks strangely detached from events, more a traveler than a central figure in the story’s unfolding drama. Her past teased early on is rarely explored in meaningful ways, and key narrative turns tend to happen around her rather than because of her.

Still, I admired what the game did show particularly its cultural influences. From architecture to enemy design, everything in Wuchang is rooted in Ming Dynasty aesthetic traditions and folklore. That might not sound groundbreaking, but it is. Too many games borrow surface elements from non-Western settings without really understanding them. Wuchang fictionalizes history, but it does so with reverence and richness. I am a big, longtime fan of Chinese historical and period and I have barely missed watching any of them; I thought I was walking through stories I didn’t fully understand, but desperately wanted to, and that’s a powerful feeling in itself in this Chinese title.

That brings me to one final point, which is the game’s visual and audio design. Wuchang: Fallen Feathers is fantastic, the art direction is painterly in the best sense, as composed. Like every screen could be framed, or scrolled across like an ancient silk tapestry. Even grotesque enemies are painted with purpose, from their corrupted feathers to the snarling, mask-like faces they wear. And the score understated but chilling knows when to whisper and when to howl. Some boss themes still echo in my mind days later.

It’s the bosses where my love-hate relationship with Wuchang reached its peak. For every elegant duel against a skillful foe, there was another that was tuned for pain more than clarity. Tight dodge windows, merciless combos, delayed hits that bait and punish reaction, it all veered into frustration at times. Mainly in the late game, I found myself respec’ing into completely different weapons only to give myself a fighting chance. That’s not necessarily bad — adaptability is part of the game’s ethos — but it did make me wonder whether the game was designed around flexibility, or patched over with it.

By the end, though, I had no regrets. My Wuchang wasn’t the same character I started with, not just mechanically, but emotionally. I’d learned her pace, power, burden. I’d stared down the worst the world could offer, and I’d overcome it not because the game made me stronger, but because it made me change. That’s the soul of any good Soulslike, and despite its missteps, Wuchang: Fallen Feathers earns its place among the memorable ones.

Verdict

For a debut effort, Leenzee Games has delivered something bold, beautiful, and, in many ways, brave. The game doesn’t always balance difficulty with grace. It struggles to tell a tight story. It sometimes leans too hard on the genre’s established motifs. But what it lacks in polish, it makes up for in ambition, mechanical creativity, and aesthetic integrity. In a crowded field of Soulslike titles, Wuchang reflects, interprets, and brings something of its own, and that’s more than enough to warrant a recommendation.